Gatsby is an incredible static site generator that allows for React to be used

as the underlying rendering engine to scaffold out a static site that truly has

all the benefits expected in a modern web application. It does this by rendering

dynamic React components into static HTML content via server side

rendering at build time. This means that your users get all

the benefits of a static site such as the ability to work without JavaScript,

search engine friendliness, speedy load times, etc. without losing the dynamism

and interactivity that is expected of the modern web. Once rendered to static

HTML, client-side React/JavaScript can take over (if creating stateful

components or logic in componentDidMount) and add dynamism to the statically

generated content.

Gatsby recently released a v1.0.0 with a bunch of new features, including (but not limited to) the ability to create content queries with GraphQL, integration with various CMSs—including WordPress, Contentful, Drupal, etc., and route based code splitting to keep the end-user experience as snappy as possible. In this post, we’ll take a deep dive into Gatsby and some of these new features by creating a static blog. Let’s get on it!

Getting started

Using the CLI

Gatsby ships with a great CLI (command line interface) that contains the functionality of scaffolding out a working site as well as commands to help develop the site once created.

gatsby new personal-blog && cd $_

This command will create the folder personal-blog and then change into that

directory. A working gatsby statically generated application can now be

developed upon. The CLI generates common development scripts to help you get started.

For example you can run npm run build (build a production, statically generated version of the project) or npm run develop (launch a hot-reload enabled web development server),

etc.

We can now begin the exciting task of actually developing on the site and

creating a functional, modern blog. You’ll generally want to use npm run develop to launch the local development server to validate functionality as we

progress through the steps.

Adding necessary plugins

Gatsby supports a rich plugin interface, and many incredibly useful plugins have been authored to make accomplishing common tasks a breeze. Plugins can be broken up into three main categories: functional plugins, source plugins, and transformer plugins.

Functional plugins

Functional plugins either implement some functionality (e.g. offline support, generating a sitemap, etc.) or they extend Gatsby’s webpack configuration adding support for TypeScript, Sass, etc.

For this particular blog post, we want a single page app-like feel (without page

reloads) as well as the ability to dynamically change the title tag within

the head tags. As noted, the Gatsby plugin ecosystem is rich, vibrant, and

growing, so oftentimes a plugin already exists that solves the particular

problem you’re trying to solve. To address the functionality we want for this

blog, we’ll use the following plugins:

gatsby-plugin-catch-links- implements the history

pushStateAPI and does not require a page reload on navigating to a different page in the blog

- implements the history

gatsby-plugin-react-helmet- react-helmet is a tool that allows for modification of the

headtags; Gatsby statically renders any of theseheadtag changes

- react-helmet is a tool that allows for modification of the

with the following command:

yarn add gatsby-plugin-catch-links gatsby-plugin-react-helmetWe’re using yarn, but npm can just as easily be used with npm i --save [deps].

After installing each of these functional plugins, we’ll edit

gatsby-config.js, which Gatsby loads at build-time to implement the exposed

functionality of the specified plugins.

module.exports = {

siteMetadata: {

title: `Your Name - Blog`,

author: `Your Name`,

},

plugins: ["gatsby-plugin-catch-links", "gatsby-plugin-react-helmet"],}Without any additional work besides a yarn install and editing a config file,

we now have the ability to edit our site’s head tags as well as implement a

single page app feel without reloads. Now, let’s enhance the base functionality

by implementing a source plugin which can load blog posts from our local file

system.

Source plugins

Source plugins create nodes which can then be transformed into a usable format

(if not already usable) by a transformer plugin. For instance, a typical

workflow often involves using

gatsby-source-filesystem, which loads files off of

disk—e.g. Markdown files—and then specifying a Markdown transformer to

transform the Markdown into HTML.

Since the bulk of the blog’s content and each article will be authored in

Markdown, let’s add that gatsby-source-filesystem

plugin. Similarly to our previous step, we’ll install the plugin and then inject

into our gatsby-config.js, like so:

yarn add gatsby-source-filesystemmodule.exports = {

// previous configuration

plugins: [

"gatsby-plugin-catch-links",

"gatsby-plugin-react-helmet",

{ resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`, options: { path: `${__dirname}/src/pages`, name: "pages", }, }, ],

}Some explanation will be helpful here! An options object can be passed to a

plugin, and we’re passing the filesystem path (which is where our Markdown files

will be located) and then a name for the source files. Now that Gatsby knows

about our source files, we can begin applying some useful transformers to

convert those files into usable data!

Transformer plugins

As mentioned, a transformer plugin takes some underlying data format that is not inherently usable in its current form (e.g. Markdown, json, yaml, etc.) and transforms it into a format that Gatsby can understand and that we can query against with GraphQL. Jointly, the filesystem source plugin will load file nodes (as Markdown) off of our filesystem, and then the Markdown transformer will take over and convert to usable HTML.

We’ll only be using one transformer plugin (for Markdown), so let’s get that installed.

- gatsby-transformer-remark

- Uses the remark Markdown parser to transform .md files on disk

into HTML; additionally, this transformer can optionally take plugins to

further extend functionality—e.g. add syntax highlighting with

gatsby-remark-prismjs,gatsby-remark-copy-linked-filesto copy relative files specified in markdown,gatsby-remark-imagesto compress images and add responsive images withsrcset, etc.

- Uses the remark Markdown parser to transform .md files on disk

into HTML; additionally, this transformer can optionally take plugins to

further extend functionality—e.g. add syntax highlighting with

The process should be familiar by now, install and then add to config.

yarn add gatsby-transformer-remarkand editing gatsby-config.js

module.exports = {

// previous setup

plugins: [

"gatsby-plugin-catch-links",

"gatsby-plugin-react-helmet",

{

resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`,

options: {

path: `${__dirname}/src/pages`,

name: "pages",

},

},

{ resolve: "gatsby-transformer-remark", options: { plugins: [], // just in case those previously mentioned remark plugins sound cool :) }, }, ],

}Whew! Seems like a lot of set up, but collectively these plugins are going to super charge Gatsby and give us an incredibly powerful (yet relatively simple!) development environment. We have one more setup step and it’s an easy one. We’re simply going to create a Markdown file that will contain the content of our first blog post. Let’s get to it.

Writing our first Markdown blog post

The gatsby-source-filesystem plugin we configured earlier expects our content

to be in src/pages, so that’s exactly where we’ll put it!

Gatsby is not at all prescriptive in naming conventions, but a typical practice

for blog posts is to name the folder something like MM-DD-YYYY-title, e.g.

07-12-2017-hello-world. Let’s do just that. Create the folder

src/pages/07-12-2017-getting-started and place an index.md inside!

The content of this Markdown file will be our blog post, authored in Markdown (of course!). Here’s what it’ll look like:

---

path: "/hello-world"

date: 2017-07-12T17:12:33.962Z

title: "My First Gatsby Post"

---

Oooooh-weeee, my first blog post!Fairly typical stuff, except for the block surrounded in dashes. What is that?

That is what is referred to as frontmatter, and the contents of

the block can be used to inject React components with the specified data, e.g.

path, date, title, etc. Any piece of data can be injected here (e.g. tags,

sub-title, draft, etc.), so feel free to experiment and find what necessary

pieces of frontmatter are required to achieve an ideal blogging system for your

usage. One important note is that path will be used when we dynamically create

our pages to specify the URL/path to render the file (in a later step!). In this

instance, http://localhost:8000/hello-world will be the path to this file.

Now that we have created a blog post with frontmatter and some content, we can begin actually writing some React components that will display this data!

Creating the (React) template

As Gatsby supports server side rendering (to string) of React components, we can write our template in… you guessed it, React! (Or Preact, if that’s more your style)

We’ll want to create the file src/templates/blog-post.js (please create the

src/templates folder if it does not yet exist!).

import React from "react"

import { Helmet } from "react-helmet"

// import '../css/blog-post.css'; // make it pretty!

export default function Template({

data, // this prop will be injected by the GraphQL query we'll write in a bit

}) {

const { markdownRemark: post } = data // data.markdownRemark holds our post data

return (

<div className="blog-post-container">

<Helmet title={`Your Blog Name - ${post.frontmatter.title}`} />

<div className="blog-post">

<h1>{post.frontmatter.title}</h1>

<div

className="blog-post-content"

dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: post.html }}

/>

</div>

</div>

)

}Whoa, neat! This React component will be rendered to a static HTML string (for each route/blog post we define), which will serve as the basis of our routing/navigation for our blog.

At this point, there is a reasonable level of confusion and “magic” occurring,

particularly with the props injection. What is markdownRemark? Where is this

data prop injected from? All good questions, so let’s answer them by writing a

GraphQL query to seed our <Template /> component with content!

Writing the GraphQL query

Below the Template declaration, we’ll want to add a GraphQL query. This is an

incredibly powerful utility provided by Gatsby which lets us pick and choose

very simply the pieces of data that we want to display for our blog post. Each

piece of data our query selects will be injected via the data property we

specified earlier.

import React from "react"

import { Helmet } from "react-helmet"

import { graphql } from "gatsby"

// import '../css/blog-post.css';

export default function Template({ data }) {

const { markdownRemark: post } = data

return (

<div className="blog-post-container">

<Helmet title={`Your Blog Name - ${post.frontmatter.title}`} />

<div className="blog-post">

<h1>{post.frontmatter.title}</h1>

<div

className="blog-post-content"

dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: post.html }}

/>

</div>

</div>

)

}

export const pageQuery = graphql` query BlogPostByPath($path: String!) { markdownRemark(frontmatter: { path: { eq: $path } }) { html frontmatter { date(formatString: "MMMM DD, YYYY") path title } } }`If you’re not familiar with GraphQL, this may seem slightly confusing, but we can break down what’s going down here piece by piece.

Note: To learn more about GraphQL, consider this excellent resource

The underlying query name BlogPostByPath (note: these query names need to be

unique!) will be injected with the current path, e.g. the specific blog post we

are viewing. This path will be available as $path in our query. For instance,

if we were viewing our previously created blog post, the path of the file that

data will be pulled from will be /hello-world.

markdownRemark will be the injected property available via the prop data, as

named in the GraphQL query. Each property we pull via the GraphQL query will be

available under this markdownRemark property. For example, to access the

transformed HTML we would access the data prop via data.markdownRemark.html.

frontmatter, is of course our data structure we provided at the beginning of

our Markdown file. Each key we define there will be available to be injected

into the query.

At this point, we have a bunch of plugins installed to load files off of disk, transform Markdown to HTML, and other utilities. We have a single, lonely Markdown file that will be rendered as a blog post. Finally, we have a React template for blog posts as well as a wired up GraphQL query to query for a blog post and inject the React template with the queried data. Next up: programmatically creating the necessary static pages (and injecting the templates) with Gatsby’s Node API. Let’s get down to it.

An important note to make at this point is that the GraphQL query takes place at

build time. The component is injected with the data prop that is seeded by

the GraphQL query. Unless anything dynamic (e.g. logic in componentDidMount,

state changes, etc.) occurs, this component will be pure, rendered HTML

generated via the React rendering engine, GraphQL, and Gatsby!

Creating the static pages

Gatsby exposes a powerful Node API, which allows for functionality such as

creating dynamic pages (blog posts!), extending the babel or webpack configs,

modifying the created nodes or pages, etc. This API is exposed in the

gatsby-node.js file in the root directory of your project—e.g. at the same

level as gatsby-config.js. Each export found in this file will be parsed by

Gatsby, as detailed in its Node API specification. However, we only

care about one particular API in this instance, createPages.

const path = require("path")

exports.createPages = ({ actions, graphql }) => {

const { createPage } = actions

const blogPostTemplate = path.resolve(`src/templates/blog-post.js`)

}Nothing super complex yet! We’re using the createPages API (which Gatsby will

call at build time with injected parameters). We’re also grabbing the path to

our blogPostTemplate we created earlier. Finally, we’re using the createPage

action creator/function made available in actions. Gatsby uses Redux

internally to manage its state, and actions are simply the exposed

action creators of Gatsby, of which createPage is one of the action creators!

For the full list of exposed action creators, check out Gatsby’s

documentation. We can now construct the GraphQL

query, which will fetch all of our Markdown posts.

Querying for posts

const path = require("path")

exports.createPages = ({ actions, graphql }) => {

const { createPage } = actions

const blogPostTemplate = path.resolve(`src/templates/blog-post.js`)

return graphql(` { allMarkdownRemark( sort: { order: DESC, fields: [frontmatter___date] } limit: 1000 ) { edges { node { frontmatter { path } } } } } `).then(result => { if (result.errors) { return Promise.reject(result.errors) } })}We’re using GraphQL to get all Markdown nodes and making them available under

the allMarkdownRemark GraphQL property. Each exposed property (on node) is

made available for querying against. We’re effectively seeding a GraphQL

“database” that we can then query against via page-level GraphQL queries. One

note here is that the exports.createPages API expects a Promise to be

returned, so it works seamlessly with the graphql function, which returns a

Promise (although note a callback API is also available if that’s more your

thing).

One cool note here is that the gatsby-plugin-remark plugin exposes some useful

data for us to query with GraphQL, e.g. excerpt (a short snippet to display as

a preview), id (a unique identifier for each post), etc.

We now have our query written, but we haven’t yet programmatically created the

pages (with the createPage action creator). Let’s do that!

Creating the pages

const path = require("path")

exports.createPages = ({ actions, graphql }) => {

const { createPage } = actions

const blogPostTemplate = path.resolve(`src/templates/blog-post.js`)

return graphql(`

{

allMarkdownRemark(

sort: { order: DESC, fields: [frontmatter___date] }

limit: 1000

) {

edges {

node {

frontmatter {

path

}

}

}

}

}

`).then(result => {

if (result.errors) {

return Promise.reject(result.errors)

}

result.data.allMarkdownRemark.edges.forEach(({ node }) => { createPage({ path: node.frontmatter.path, component: blogPostTemplate, context: {}, // additional data can be passed via context }) }) })

}We’ve now tied into the Promise chain exposed by the graphql query. The actual

posts are available via the path result.data.allMarkdownRemark.edges. Each

edge contains an internal node, and this node holds the useful data that we will

use to construct a page with Gatsby. Our GraphQL “shape” is directly reflected

in this data object, so each property we pulled from that query will be

available when we are querying in our GraphQL blog post template.

The createPage API accepts an object which requires path and component

properties to be defined, which we have done above. Additionally, an optional

property context can be used to inject data and make it available to the blog

post template component via injected props (log out props to see each available

prop!). Each time we build with Gatsby, createPage will be called, and Gatsby

will create a static HTML file of the path we specified in the post’s

frontmatter—the result of which will be our stringified and parsed React

template injected with the data from our GraphQL query. Whoa, it’s actually

starting to come together!

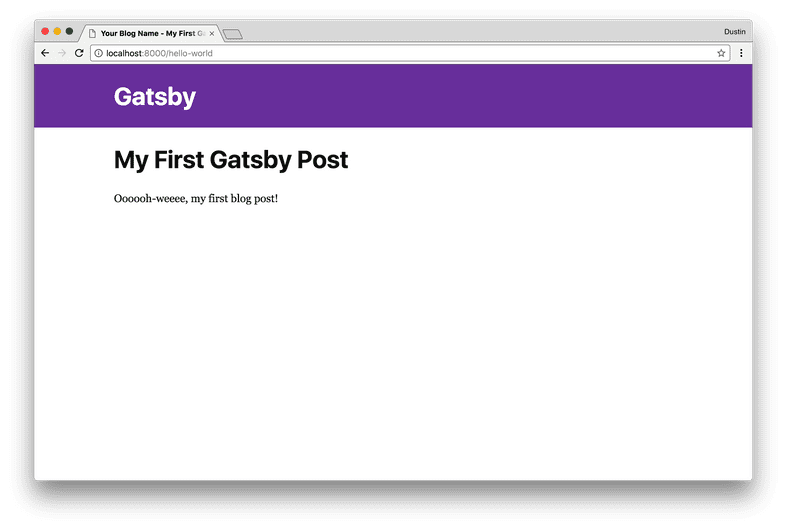

We can run yarn develop at this point and then navigate to

http://localhost:8000/hello-world to see our first blog post, which should

look something like below:

At this point, we’ve created a single static blog post as an HTML file, which was created by a React component and several GraphQL queries. However, this isn’t a blog! We can’t expect our users to guess the path of each post, we need to have an index or listing page, where we display each blog post, a short snippet, and a link to the full blog post. Wouldn’t you know it, we can do this incredibly easily with Gatsby, using a similar strategy as we used in our blog template, i.e. a React component and a GraphQL query.

Creating the Blog Listing

I won’t go into quite as much detail for this section because we’ve already done something very similar for our blog template! Look at us, we’re pro Gatsby-ers at this point!

Gatsby has a standard for “listing pages,” and they’re placed in the root of our

filesystem we specified in gatsby-source-filesystem, e.g.

src/pages/index.js. So, create that file if it does not exist, and let’s get it

working! Additionally, note that any static JavaScript files (that export a React

component!) will get a corresponding static HTML file. For instance, if we

create src/pages/tags.js, the path http://localhost:8000/tags/ will be

available within the browser and the statically generated site.

import React from "react"

import { Link, graphql } from "gatsby"

import { Helmet } from "react-helmet"

// import '../css/index.css'; // add some style if you want!

export default function Index({ data }) {

const { edges: posts } = data.allMarkdownRemark

return (

<div className="blog-posts">

{posts

.filter(post => post.node.frontmatter.title.length > 0)

.map(({ node: post }) => {

return (

<div className="blog-post-preview" key={post.id}>

<h1>

<Link to={post.frontmatter.path}>{post.frontmatter.title}</Link>

</h1>

<h2>{post.frontmatter.date}</h2>

<p>{post.excerpt}</p>

</div>

)

})}

</div>

)

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query IndexQuery {

allMarkdownRemark(sort: { order: DESC, fields: [frontmatter___date] }) {

edges {

node {

excerpt(pruneLength: 250)

id

frontmatter {

title

date(formatString: "MMMM DD, YYYY")

path

}

}

}

}

}

`OK! So we’ve followed a similar approach to our blog post template, so this

should hopefully seem pretty familiar. Once more we’re exporting pageQuery

which contains a GraphQL query. Note that we’re pulling a slightly different

data set — specifically, we are pulling an excerpt of 250 characters rather than

the full HTML as we are formatting the pulled date with a format

string! GraphQL is awesome.

The actual React component is fairly trivial, but one important note should be

made. It’s important that when linking to internal content, e.g. other blog

links, that you should always use Link from gatsby. Gatsby does not work if pages

are not routed via this utility. Additionally, this utility also works with

pathPrefix, which allows for a Gatsby site to be deployed on a non-root domain.

This is useful if this blog will be hosted on something like GitHub Pages or

perhaps hosted at /blog.

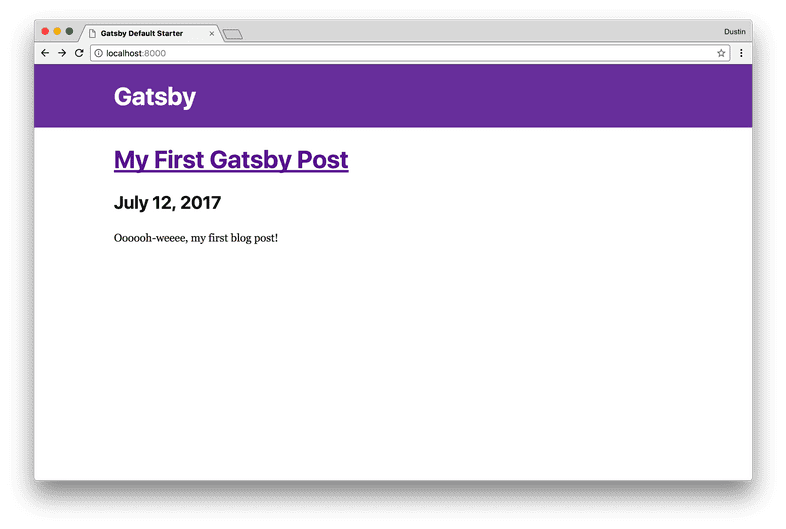

Now, this is getting exciting and it feels like we’re finally getting somewhere!

At this point, we have a fully functional blog generated by Gatsby, with real

content authored in Markdown, a blog listing, and the ability to navigate around

in the blog. If you run yarn develop, http://localhost:8000 should display a

preview of each blog post, and each post title links to the content of the blog

post. A real blog!

It’s now on you to make something incredible with the knowledge you’ve gained in following along with this tutorial! You can not only make it pretty and style with CSS (or styled-components!), but you could improve it functionally by implementing some of the following:

- Add a tag listing and tag search page

- hint: the

createPagesAPI ingatsby-node.jsfile is useful here, as is frontmatter

- hint: the

- adding navigation between a specific blog post and past/present blog posts

(the

contextAPI ofcreatePagesis useful here), etc.

With our new found knowledge of Gatsby and its API, you should feel empowered to begin to utilize Gatsby to its fullest potential. A blog is just the starting point; Gatsby’s rich ecosystem, extensible API, and advanced querying capabilities provide a powerful toolset for building truly incredible, performant sites.

Now go build something great.

Links

@dschau/gatsby-blog-starter-kit- A working repo demonstrating all of the aforementioned functionality of Gatsby

@dschau/create-gatsby-blog-post- A utility and CLI I created to scaffold out a blog post following the predefined Gatsby structure with frontmatter, date, path, etc.

- Source code for my blog

- The source code for my blog, which takes the gatsby-starter-blog-post (previous link), and expands upon it with a bunch of features and some more advanced functionality